|

Hats

were elaborate -- richly ornamented and embroidered. Married women wore

them on the street and at home, unmarried women didn't. Men wore hats

indoors too, and uncovered when the Queen entered or left a room. Early

Elizabethan hats were tall steeple hats, or conical "copintakes"

and the low-crowned wide-brimmed or unbrimmed hat was also very popular.

The brimmed type was, in the next century, adopted by the Cavaliers.

Hats were made of velvet, silk, taffeta, beaver and ermine. Coifs, hoods,

cauls, and caps were also worn...

Men

no less than women went in for elaborate and complicated dress and often

wore a fortune on their backs. The whole point of the Ralegh story is

that a man's cloak was frequently the most valuable part of his wardrobe,

costing hundreds of pounds....

Another

gentlemen, Robert Sidney, in a letter to John Harrington describes the

dress he wore the day Elizabeth visited him....He was clad, he says,

"in a rich band and collar of needlework, a dress of rich stuff

and bravest-cut and fashioned with an underbody

of silver and loops."

Men,

almost as much as women, were given to the use of cosmetics, and were

as vain about the cut and colour of a beard as they were about the cut

and colour of doublet and hose. Harrison, in the middle of a "dry

mock" on fashions in dress, drops in a "bitter taunt"

or two about masculine beard- and hair-styles. "I say nothing of

our heads" he remarks-with paralipsis worthy of Mark Antony--"which

sometimes are polled, sometimes curled or suffered to grow at length

like woman's locks, many times cut off, above or under the ears,

round as by a wooden dish. Neither", says he, "will I meddle

with our variety of beards" and then meddles delightfully.

Some were "shaven from the chin like those of Turks"; others

were cut short like that of Marquess Otto, or rounded like a "rubbing

brush". Some had the "pique de vant", others were  allowed

to grow long. Barbers, on the whole, the parson says, were as cunning

as tailors when it came to making a beard alter the shape of a face

or cover some fancied facial defect. The long, lean, straight face could

be made to look broad and large by a Marquess Otto cut. The owner of

a 'platter-liken face need not be too unhappy, as a long narrow

beard quite altered the flat, plate-like look. For the "weasel-becked",

much hair left on the cheeks would make the owner look "big like

a bowdled-hen and as grim as a goose.. These seem singularly unattractive

alternatives; there can be little to choose between resembling a stoat

or a barnyard fowl. Harrison, too, strikes the note that all this --

and all this included the wearing of earrings of gold set with stones

and pearls -- is an offence to the Lord since men were attempting to

amend the faces God gave them. allowed

to grow long. Barbers, on the whole, the parson says, were as cunning

as tailors when it came to making a beard alter the shape of a face

or cover some fancied facial defect. The long, lean, straight face could

be made to look broad and large by a Marquess Otto cut. The owner of

a 'platter-liken face need not be too unhappy, as a long narrow

beard quite altered the flat, plate-like look. For the "weasel-becked",

much hair left on the cheeks would make the owner look "big like

a bowdled-hen and as grim as a goose.. These seem singularly unattractive

alternatives; there can be little to choose between resembling a stoat

or a barnyard fowl. Harrison, too, strikes the note that all this --

and all this included the wearing of earrings of gold set with stones

and pearls -- is an offence to the Lord since men were attempting to

amend the faces God gave them.

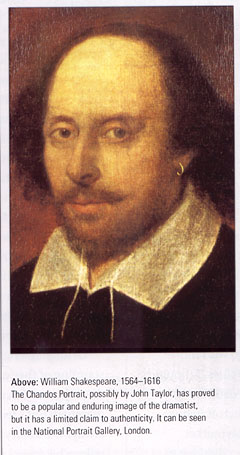

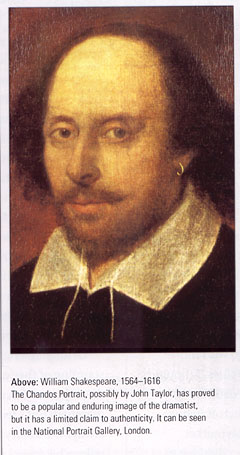

Shakespeare's

Hotspur was impatient of the Elizabethan dandy. "Popinjays"

he calls them and describes, for the benefit of Henry IV, how, after

the battle of Holmedon when he was himself breathless, faint, dry with

rage and toil

"Came

there a certain lord, neat, and trimly dress'd,

Fresh as a bridegroom; and his chin, new reap'd

Showed like a stubble-land at harvest home;

He was perfumed like a milliner,

And 'twixt his finger and his thumb he held

A pouncet-box which ever and anon

He gave his nose..."

Excerpted from "The Pageant of Elizabethan

England" by Elizabeth Burton

|

allowed

to grow long. Barbers, on the whole, the parson says, were as cunning

as tailors when it came to making a beard alter the shape of a face

or cover some fancied facial defect. The long, lean, straight face could

be made to look broad and large by a Marquess Otto cut. The owner of

a 'platter-liken face need not be too unhappy, as a long narrow

beard quite altered the flat, plate-like look. For the "weasel-becked",

much hair left on the cheeks would make the owner look "big like

a bowdled-hen and as grim as a goose.. These seem singularly unattractive

alternatives; there can be little to choose between resembling a stoat

or a barnyard fowl. Harrison, too, strikes the note that all this --

and all this included the wearing of earrings of gold set with stones

and pearls -- is an offence to the Lord since men were attempting to

amend the faces God gave them.

allowed

to grow long. Barbers, on the whole, the parson says, were as cunning

as tailors when it came to making a beard alter the shape of a face

or cover some fancied facial defect. The long, lean, straight face could

be made to look broad and large by a Marquess Otto cut. The owner of

a 'platter-liken face need not be too unhappy, as a long narrow

beard quite altered the flat, plate-like look. For the "weasel-becked",

much hair left on the cheeks would make the owner look "big like

a bowdled-hen and as grim as a goose.. These seem singularly unattractive

alternatives; there can be little to choose between resembling a stoat

or a barnyard fowl. Harrison, too, strikes the note that all this --

and all this included the wearing of earrings of gold set with stones

and pearls -- is an offence to the Lord since men were attempting to

amend the faces God gave them.

hung with rich tapestry

of pure gold and fine silks, so exceedingly beautiful and royally ornamented

that it would hardly be possible to find more magnificent things of

the kind in any other place. In particular, there is one apartment belonging

to the Queen, in which she is accustomed to sit in state, costly beyond

everything; the tapestries are garnished with gold, pearls and

precious stones, one table-cover alone is valued at above fifty thousand

crowns--not to mention the royal throne studded with very large

diamonds, rubies, sapphires and the like that glitter among other precious

stones and pearls as the sun among the stars."...

hung with rich tapestry

of pure gold and fine silks, so exceedingly beautiful and royally ornamented

that it would hardly be possible to find more magnificent things of

the kind in any other place. In particular, there is one apartment belonging

to the Queen, in which she is accustomed to sit in state, costly beyond

everything; the tapestries are garnished with gold, pearls and

precious stones, one table-cover alone is valued at above fifty thousand

crowns--not to mention the royal throne studded with very large

diamonds, rubies, sapphires and the like that glitter among other precious

stones and pearls as the sun among the stars."...